by Yia Vang

The following is a chapter from Yia Vang’s cookbook memoir showcasing Hmong food and her experience as a first generation Hmong American learning to cook from her mom.

Growing up, I avoided doing much to help with the cooking and cleaning around the house. But when I got to high school, Mom declared that it was time for me to learn to make rice.

“Yia, you have to learn how to make Cub Mov. How are you going to find a husband if you can’t make rice?” she said in Hmong, sounding impatient.

“I don’t plan to marry a Hmong man,” I bit back, matching her agitation.

“That’s right, you’ll live off of Big Macs,” she sassed right back. “I’ll teach you how to make it. Go!” She commanded. Mom was not one to ask me what I wanted to do. Having raised fifteen children, she learned that if she wanted anything done, she needed to give directives, not options.

Mom married Dad at a young age, and she wasn’t given options. Dad was a widower who already had six children, some of whom were older than Mom. He had arrived at her village with the intention of marrying a widow, but the elders told him it wouldn’t be good for him to marry the widow. They told him to marry another woman. Mom was the youngest of six daughters. The elders of Dad’s family spoke to Mom’s parents, and before she knew it, they told her she was going to marry Dad. She had no say in the matter; it was done. They had the wedding, and after trekking through the mountains of Laos for three days, she found herself in Dad’s village: a wife and mother.

How to make Cub Mov (steam rice) as taught by Mom:

Yield: A family of nine

Prep time: the night before serving the rice

Cook time: the day one serves the rice

Ingredients:

Rice

Water

Memory

Equipment:

Bowl

Two-piece steamer that includes a pot and the bamboo steamer with a lid

Another pot of boiling water

Steps:

1. Use your senses

I head to the kitchen with mom behind me.

“Get the big bowl from the cupboard and fill it with rice.”

“How many cups?” I ask.

“How many cups?” She repeats, confused by the question.

“Yes, Mom, how many cups do you want?”

“Just fill the bowl halfway,” she says.

To Mom, there are no cups, quarts, or liters. There are no tablespoons or teaspoons, grams or ounces. She cooks with her senses. Mom learned how to cook from watching her mother and sisters. She grew up observing and imitating them, tasting the food they made, doing it precisely the way they did it. Mom’s measuring tools are her senses, and they tell her the exact amount that is needed, the exact length that something needs to be cooked for. Her nose knows the smell of a dish when it’s done, or how much longer it needs to cook. Her tongue becomes a cookbook. When Mom tastes food, I can almost see her tongue turn to the right page to make sure she’s added the amount called for.

I use a cup to scoop rice into the bowl and show it to her.

“Too much.”

That was halfway, I think, but don’t dare say anything. I pour some back in the bin and show her the bowl again. This time she nods.

2. Live with the cycles

“Now wash the rice.”

I take the bowl to the sink and run some cold water through it, splashing my hand in the bowl and twirling the rice around.

“No, not like that. Wash it,” she walks over to stand beside me. “Like this,” she dips both hands into the bowl, scoops up the rice and brushes her right hand over her left as the rice between her hands falls back into the bowl. She does this a few more times. The water is now a milky white.

“Now drain the rice, put in fresh water, and do it again.”

I do as I’m told. Once the bowl is filled up with water, I imitate her actions.

“Not so hard. You’ll break the rice. Don’t rub it. Just brush one hand over the other.”

Again, I follow, this time brushing, not rubbing. I do it a few times, the color turning milky again but this time a lighter color.

“How many times do I do this?”

“Just keep doing it until the white washes away and the water is clear.”

To Mom, time is not linear. She doesn’t do something X number of times for a guaranteed result. She doesn’t calculate her actions, her success, her future. Life was never laid out in front of her to have a job by 22, a husband at 28, and her first child by 30. When dad took her home, she didn’t know how old she was. She grew up with the waning and waxing of the moon, with the cycles of harvest seasons. One season fell into the other. She grew up with pots and pans as her toys, thread and needle and fabric as her writing tools and books. The acres of land where the food was grown, was also her playground. She tilled, planted, harvested, slashed and burned, tilled again. There were no calendars, no age, no instruction manuals to tell her how and when to do something. She responded to the moon, the seasons, her family’s needs.

I proceed to drain the water, fill and wash the rice again, brushing one hand over the other. This time I feel the individual grains, cool and gritty to the touch, tickling my palms as they brush against each other. Water runs between my fingers, sliding back down into the bowl. My hands dip into the cold, thick pool of sand.

After a few more rounds, the water remains clear.

Mom tells me to stop and now fill the bowl with water to the top. Leave the rice to soak overnight.

3. Stay in the Flow

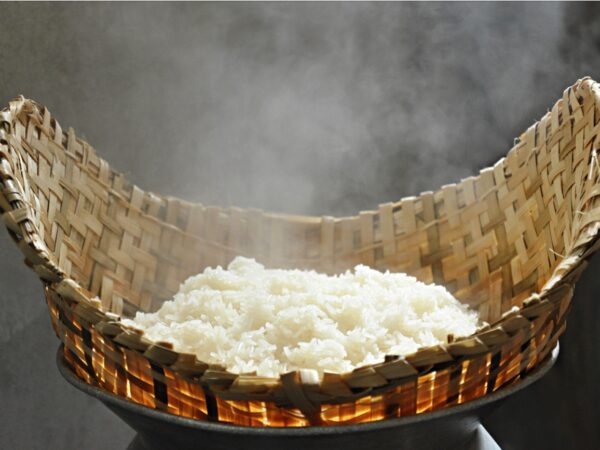

The following morning, Mom wakes me up at 7 am to continue the preparation. She tells me to get out the bamboo steamer and pot. Fill the pot to where there’s already a water mark. The bamboo steamer looks like a cone, an oriental straw hat, like the ones in movies that Asians wear while working in the rice fields. We drain the soaked rice and pour it into the steamer, cover it with the lid, and put it in the pot. The steamer catches the rim of the pot about a quarter of the way in and sits there. There is already a second pot on the stove that’s filled with the boiling water we’ll need for soaking the rice again after it’s cooked.

“How long does rice steam for?” I ask her. “How many minutes?” I’m ready to set a timer and go sit down to watch some Saturday morning cartoons.

“Thawm cov mov tuaj, tes muab phoo.” “When the rice arrives, take it out to soak in the boiling water.” When the rice arrives? I have no idea what that means. Hasn’t the rice been there the whole time? Where is it arriving from?

I ask her how do you know when the rice has arrived?

“Just watch and you will know,” she responds.

Mom has no alarm clock to wake her up. Her body naturally rises with the sun and sleeps with the moon. She stays in the flow from the moment of wake up until her eyes close at night. In Laos, she woke up before the first crow of the rooster to start a fire on her hearth. The fire lit up the bamboo house to awaken her children. She boiled water for the rice. With only one fire available to cook the day’s meal, it was important to get an early start so that food would be ready shortly after sunrise. Then they ate, packed lunch, and set out for the acres of land that needed tending. There was no rest, no checking out, no waiting for an alarm to tell her to do the next thing.

I keep my eyes on the steamer, looking for an announcement of the rice’s arrival. A cloud of steam starts to shoot out from the bamboo container and evaporates into the air.

After some time has passed, Mom says, “Now it’s arrived.” She instructs me to pour the rice from the bamboo steamer into the big bowl she’s put on the counter. It crumbles into tiny grains. Now we pour the boiling water from the second pot over the rice until it reaches just to the top of the grains. As I pour, the mountain of rice avalanches into a pool of hot water. Having been on a long journey to arrive at this moment, the grains quickly drink up its warmth.

4. Be in Relationship

Mom tells me that the waiting, the patience, is the most important part of rice making — now we soak. When the rice soaks, don’t let it sit too long, otherwise it’ll become mushy, and if you don’t soak it long enough it’ll be hard. Once again, there is no timer. Everything is done with the eyes, taste, senses. Midway through soaking, turn the rice over once to bring the bottom rice to the top so that the top rice gets a chance to drink, to bathe. During the turning, do not do it too hard or stir the rice, otherwise it will break. This process requires soft confident hands. Once the rice has been flipped, let it sit again. When the rice has had enough to drink, meaning that all water is gone, scoop it back into the bamboo steamer and cover it up. Add more water to the pot so that it doesn’t dry out, and put the steamer back in the pot over the stove.

I do as instructed, paying attention to Mom’s words. I want to ask her “how do you know how much water to pour in, how do you know when the rice is cooked and how long does it steam for,” but I don’t ask. Instead, I pay attention to her instructions, and I watch.

Mom learned not by asking questions, but simply by observing the rice changing color, texture, and shape from one phase to the next. She became intimate with her environment, with the six children she had to raise and nine more of her own. She became intimate with the crops she planted and harvested, knowing each one by color and texture and smell and the intricate ways they told her when it was time to pick them.

Mom knows which herbs to use for the classic medicinal Hmong chicken soup “qhaij nqab” that she had to eat for a month to cleanse her body after giving birth to each baby.

Mom knows the herbs to use and how to prepare for when, one day playing dodgeball, I tripped on the ball, fell, and sprained my arm. That day, she picked the herbs, chopped them, put them on a cloth and wrapped them with aluminum foil to heat over the stove. The herbs smelled of dark earth—green, pungent. She kept the swelling down, and three days later, after refreshing a new batch of herbs each morning, my arm healed; no doctor or cast needed. She carried that relationship with her herbs to the US, and even when we were eleven people crammed into a two-bedroom apartment with no yard, she still found a way to plant herbs in buckets in front of the house and make the back dirt area into a garden that made the other Hmong mothers follow suit and create their own little piece of homeland in America.

5. Noj Mov!

As the rice steams for a second time, I watch for signs of when it’s ready. During this time, I finish putting away dishes and scramble some eggs for us, while Mom tends to her chicken soup and kabocha squash broth. I set the table with plates and spoons, napkins and hot pepper. I keep my eye on the rice, and eventually the second wave of steam starts to shoot out of the steamer. The sweet aroma of rice starts to fill the house. A few minutes later Mom tells me the rice is ready. I still don’t understand how she knows. I take the steamer out, and she tells me to pour rice into a clean bowl. I tip the steamer, and a mountain of rice plops down into the bowl. Each grain looks proud, plump, pearly white. This time the grains hold on to each other on the way down, forming lumps, but you can easily see each separate grain. Mom tells me to fluff the rice and let the steam out, then scoop some into a smaller bowl for the table. The rest goes in the rice cooker to keep warm for the day. When I plug in the rice cooker, the keep-warm light comes on.

I bring the smaller bowl to the table, scoop out chicken soup into two bowls, the Kabocha squash broth into two bowls, the scrambled eggs onto two platters and arrange them on the table. The proud rice is the center piece, bringing all the other dishes together.

I do a quick round throughout the house, tell everyone to “noj mov!” This literally translates to let’s eat rice!

I sit down at the table, scoop rice onto my plate and the eggs next to it. Rice with any dish creates a symphony of flavors, sometimes blending them in perfect harmony, other times highlighting the contrast. I take a spoonful of rice with the eggs, blow on it lightly to cool before putting it in my mouth. The lump of rice is warm, soft; each grain dances in my mouth as I chew. The rice teases my tastebuds, slightly sweet and delicate, but earthy, plump, and moist — mixed with the salty dry thickness of eggs. As I swallow my mother’s instructions, I realize that this is the taste of her love.

Get access to the monthly Rehumanization Magazine featuring contributors from the front lines of this effort—those living on Death Row, residents of the largest women’s prison in the world, renowned ecologists, the food insecure, and veteran correctional officers alike.

Get access to the monthly Rehumanization Magazine featuring contributors from the front lines of this effort—those living on Death Row, residents of the largest women’s prison in the world, renowned ecologists, the food insecure, and veteran correctional officers alike.