by Matt Sherman

–

Matt Sherman is a member of the BlackBox collective. An initiative of Unconditional Freedom, BlackBox is a group dedicated to guiding black people towards expressing power by claiming our value. Through contemplative practices, telling our stories, questioning the culture, and creating a space for discussions, we desire to liberate our culture’s collective voices and each individual soul’s unique expression. We are a movement toward the reclamation of the innate power of Blackness, our value, our gifts, and how to bring them to humanity in a way that creates new black power and unconditional freedom.

Bare feet. Fruit falling and some still hanging. This apple tree feels like I’m in Eden. The tree of life without the serpent. I think about how it was innate for my ancestors to come to the trees, to know the time for planting them, for eating from them. We’ve become so disconnected from the source of our food. The grocery store lines its walls with pictures of trees. The actual rooted one has too many stories to tell. Safer to just take in an image. Don’t have to think about the “blood on the leaves, blood on the roots, black bodies swinging.” -Billie Holiday

My ancestors had a very violent history associated with the land in the U.S., and simultaneously were deeply connected to the land and nature prior to and even through those times. We are not that far removed from that. That connection is still in us. Many of us think we are above the land now. We often cite that history as our reason for disconnecting from it. Saying I have trauma around the land, farming, gardening, working with the soil and the sun at this stage for me feels more like caring too much about what people think. We speak on it like our history is this deep-rooted disease, like a superworm coiled up in us, eating away at our ability to connect with nature.

My feet connect to the ground more when I consider this history. I feel the earth run up through my body. Confronted, I feel more like I should come closer instead of farther away. Somewhere along the way we decided it was a privilege and status symbol to have other people handle our growth for us. Let them sweat. Get sunburnt. We have graduated from this lowly position. But this is our inheritance: Get to know the family, the fruit, the branches, the trunk, the roots, and how deep they go.

I wonder if the people just need access to this experience and then they too can know? They’d just have to get over the slave jokes from other black folks, the self-perception of being less than, and all that comes with toiling in the sun.

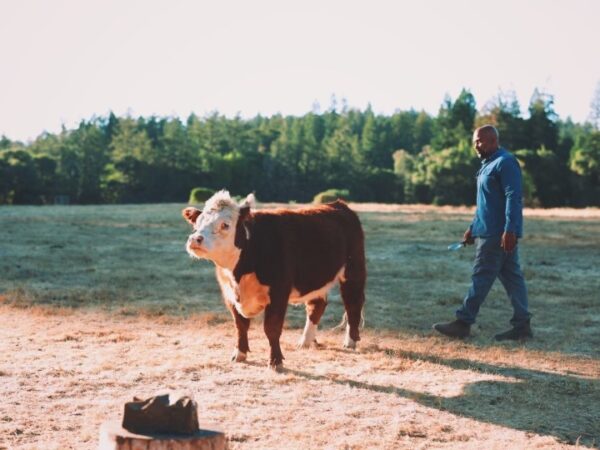

I recently started to work on the land myself. I tend to chickens, cows, and harvest apples, pears, peaches. I wear this hat that some love and some hate. My friend taunts me, saying has me look like I’m an actor in the film 12 Years a Slave.

I moved past the jokes and realized that what I’m doing is building a connection with what endures. The land holds our history and future: what could be more important? I search my belly for that trauma parasite, but all I find is self-consciousness that the land is my inheritance and a source of greatness.

For my parents, the land became a place where they were able to ensure their independence and resilience. My mother and father found their home in the old railroad working neighborhood of 5 Points, North Carolina. The house was located on a street named after the prominent leader of the Democratic “White Supremacist” campaigns, Governor Charles B. Aycock. (Street name officially changed to Roanoke recently due to petitions and protest from the new generation of neighbors.) This neighborhood would eventually become one of the most expensive areas to live in the city, which gave my parents leverage in their older years to have the freedom to not worry about shelter, income, or having something of value.

The house came complete with much work to be done and a decent sized, hilly lot next door that could fit another house — that little piece of land would eventually house my mother’s vegetable garden.

My mother tilled the soil, planted the vegetables. No lecherous tapeworm of trauma ate at her. She loved the land; this was her sanctuary.

Years went by and that hill never became that same vegetable garden again, but my mother’s green thumb didn’t stop. She cared for azaleas, tiger lilies, and a majestic Chinaberry tree in the front yard that shaded the house and provided endless entertainment as squirrels ate berries and got tipsy. My dad would construct a “clubhouse” in the backyard among the oaks, where my friends and I would escape into magical games, grill hot dogs, and roll up cardboard to smoke as if it was a cigar we’d seen in the movies. I shot BB guns and experienced my power to take a life when I shot a little sparrow minding its own business. I felt sadness and regret. I experienced my humanity. This land was teaching through these moments.

Builders would knock on their door and call and leave notes trying to buy the property, but they remained settled in having the freedom and connection to this piece of land.

My mother, now retired, spends her days with the soil, the flowers, the little statues and sculptures we’ve all sent her for her personal arboretum. New generations of families and residents in the neighborhood walk by and take photos of the landscaping, commenting on the beauty, contributing to their happiness. I can feel my mother’s joy and genius come out in the garden. The freedom to spend her days as she chooses in nature. She knows exactly where she’s at home, and it’s a place I can always call home.

The land, the soil, the Chinaberry tree, the ancient Oaks have been with us all along, teaching and providing the setting for our story of freedom and family.

Get access to the monthly Rehumanization Magazine featuring contributors from the front lines of this effort—those living on Death Row, residents of the largest women’s prison in the world, renowned ecologists, the food insecure, and veteran correctional officers alike.

Get access to the monthly Rehumanization Magazine featuring contributors from the front lines of this effort—those living on Death Row, residents of the largest women’s prison in the world, renowned ecologists, the food insecure, and veteran correctional officers alike.